Life (and life writing) lessons from a WSJ obituary writer

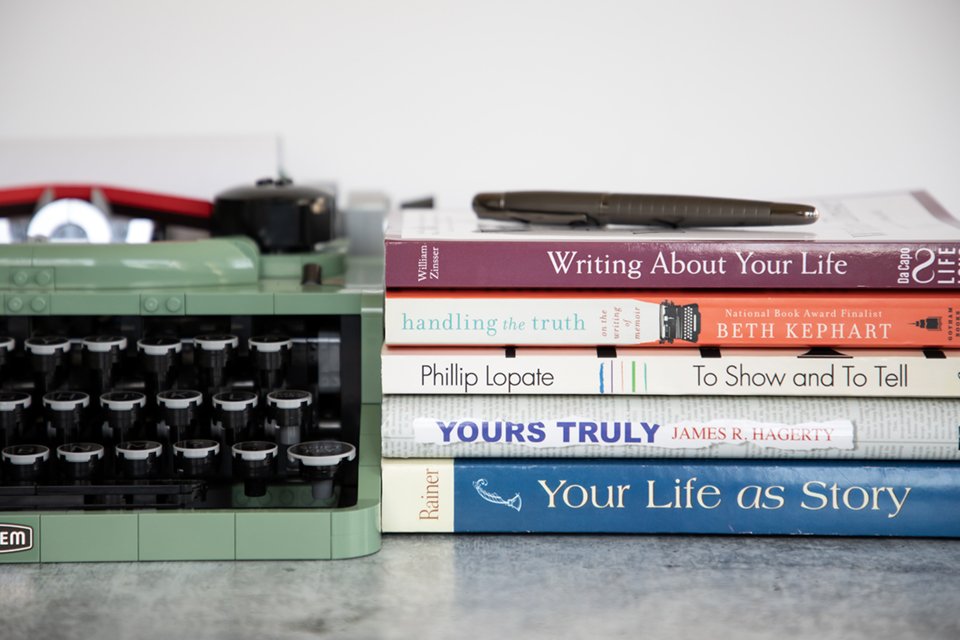

James Hagerty, a longtime obit writer for the Wall Street Journal, shares his years’ worth of life writing wisdom in the book Yours Truly: An Obituary Writer’s Guide to Telling Your Story.

There are many reasons I recommend picking up a copy of the book Yours Truly: An Obituary Writer’s Guide to Telling Your Story by James R. Hagerty. Among them: his flair for telling a good old, draw-you-right-in story, honed over decades as a reporter; his ability to distill a lifetime’s worth of living into a manageable piece of writing that is both enlightening and engaging; and his respect for everyday folks whose names we might not otherwise know had he not shined a light on them on the Wall Street Journal obituary pages (and now, in this book).

Most of all, though, I recommend you read Yours Truly to glean some life writing wisdom for yourself. My hope, like Hagerty’s, is that it will put you on the path to writing your own mini-memoir long before your family needs to craft your obituary.

For now, here are five lessons derived from the book to spark your inspiration.

Your family wants your stories—even if they seem disinterested now.

Have you ever been to a funeral, a wake, or shiva and witnessed how hungry the family members of the deceased are for stories—for any and every little morsel of memory about their lost loved one? I have. And I have also been the grieving individual desperate for such recollections.

In my years of creating tribute books to help people memorialize their lost loved ones, I am continually saddened by the regrets my clients express: regrets for not asking as many questions about their family member’s life as they “should have”; regrets for not expressing their feelings and gratitude before it was too late.

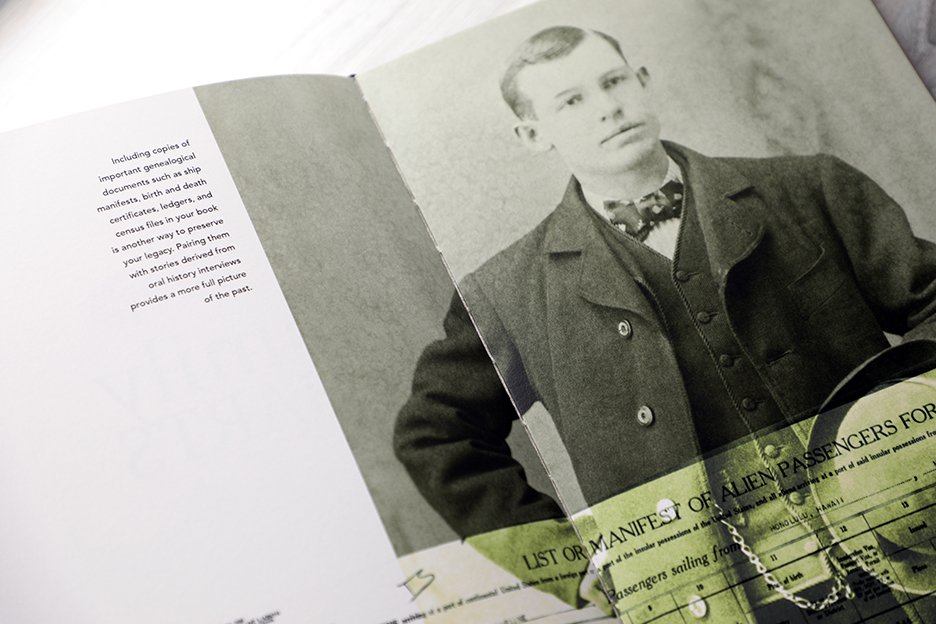

As Hagerty shares in his book, it’s often not until someone sits down to write an obituary that they realize how limited their knowledge is. “I am struck by how much [family members of the deceased] care about ensuring their loved one’s life will be remembered—and by how little they know about that life.”

This, by the way, is in no way laying blame—we all fall into this trap of taking our loved ones for granted, of thinking of them as “mom” and “dad” without really reflecting on them as individuals with rich lives of their own. Even professional personal historians like myself have felt this way—heck, it’s the reason many of us came to do what we do.

Hagerty, too, expresses: “Even if I had tried to write [my father’s] story, I would have struggled. I lived in my father’s house for my first 18 years and saw him at least once a year for the next 20-some. How can it be that I knew so little about him? Even the basic facts are blurry.” Of course he regrets not knowing more, not asking more—and it’s only in hindsight that he wishes his dad told his story—“I’m sure we would have read every word and kept it in a safe place,” he writes.

Just because your family members aren’t asking for your stories now doesn’t mean they won’t want them someday. They will, I promise.

You’ve got stories worth telling—really.

“My life is boring.”

“Ugh, I don’t have any stories—just scattered memories here and there.”

“I’ve lived a simple life, not worth talking about.”

I’ve heard all the excuses for not writing about your life and, frankly, they’re rubbish. I have yet to meet a person who felt this way who didn’t ultimately go on and on about their experiences during a personal history interview, only to surprise themselves with just how wonderful their life has been! Sure, it may take a while for some people to get warmed up, but by asking them the right questions and leading them on a path of self-discovery through reminiscence, they inevitably rediscover just how riveting their life has been.

You can “find” your stories through writing, too, and in his book, Hagerty brilliantly walks you through how to do just that. As he says, “If you think your life has been uneventful, think again. Once you start writing, you may find it’s been far more interesting than you realized.”

In addition to offering up three questions you should ask yourself before embarking on any autobiographical writing, Hagerty shares plenty of examples of life writing that will showcase just how fascinating so-called “regular” people can be—and trust me, there’s a lot to be gained by reading about the lives of others if you want to write about your own!

Recounting tough times is as important as sharing happy memories.

This is a topic I address with every person I work with: Yes, the happy memories and funny stories should go into your book—but your challenges, your failures, and your resilience must be there, too. It’s those stories that may one day provide comfort or guidance to one of your children. It’s those stories that show your humanity and that inspire.

Just as I encourage my subjects during personal history interviews, Hagerty too encourages his readers to go beyond describing episodes from your life to find meaning among them. Be thoughtful about what an experience meant to you, about what lessons you learned. Place these episodes from your life in a broader context.

“The experiences that shaped you are often what other people least understand and would be most interested to know.” Yes!

And don’t just think about recent milestones from your life. Hagerty notes that “the most common error I see in obituaries is to underestimate the importance of childhood and teenage years, and the struggles to find a career, a mate, a vocation, or a purpose in life.” It’s during those formative years that some of our biggest—life-defining!—decisions are made. They are worth exploring in a loved one’s obituary and in your own memoir writing.

“In life stories, generic will never do.”

We’ve all heard the maxim Show, don’t tell. Paint a picture of the environment you describe. Be specific about place names and clothing styles. Choose details that reveal your specific experience—including details of our modern life, for what we take for granted today may one day seem dated, even quaint: corded phones, drive-in movie theaters, and handwritten (mailed!) letters seem like relics of the past, but even more recent references to sending someone a message via a pager, hanging out at the mall, or picking your “top 8” in MySpace are already “of their time.”

This doesn’t, of course, mean to flood your stories with details, but choose telling ones, and be specific when it counts. If you are talking about your first job, describe the company and your role with real examples. If you say you felt demeaned at work, share a representative episode that made you feel that way. Allow your readers to imagine themselves experiencing life alongside you.

“Without details,” Hagerty writes, “a story shrivels into oblivion.”

Something is better than nothing.

I’ve said to many a personal history client, “Done is better than perfect.” So, too, is something better than nothing.

I am grateful for the few things my mom hand wrote in the memory journal she kept on her bookshelf. She answered about 10 of the 100 or so prompts with a mere sentence or two—and while I wish she wrote more, I cherish those sentences.

“You may never finish the project,” Hagerty writes. “That’s okay. An imperfect, incomplete story, offering whatever you can to muster to explain yourself and share the lessons you’ve learned is a precious gift to your friends, loved ones, and maybe even posterity in general. As for the memories you will resurrect and the insights into living you may discover, those are gifts to yourself.”

It’s a gift to your family, as well. A gift of legacy they will assuredly keep in a safe space in their home, and in their hearts.

Note: This is an unsolicited review of a book I purchased at full price. I did not receive any compensation or free products in exchange, and any endorsements within this post are my own.

Affiliate disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, we may earn commissions from qualifying purchases from Amazon.com.

You start out with excitement and fervor—blank pages are feverishly filled with stories about your life. But what can you do when your memoir momentum wanes?