What to cut from your memoir—when an editor and writer disagree

This is a three-part series about choices I wish my clients hadn’t made during their personal history book projects. (For what it’s worth: in my first draft of this post, I referred to “mistakes” I wish my clients hadn’t made—and then I remembered, memoir is, by definition, a personal accounting of one’s life, and far be it for me to dictate a writer’s personal preferences.) That said, clients come to me not only for help finishing the projects they envision, but for my expertise in elevating their projects to be the best they can be. So, I thought sharing a few of these differences of opinion might be instructive for those waffling over similar decisions.

Challenge 1: Should I include “the hard stuff” from my life in my memoir?

Challenge 2: Should I include a family tree in my life story?

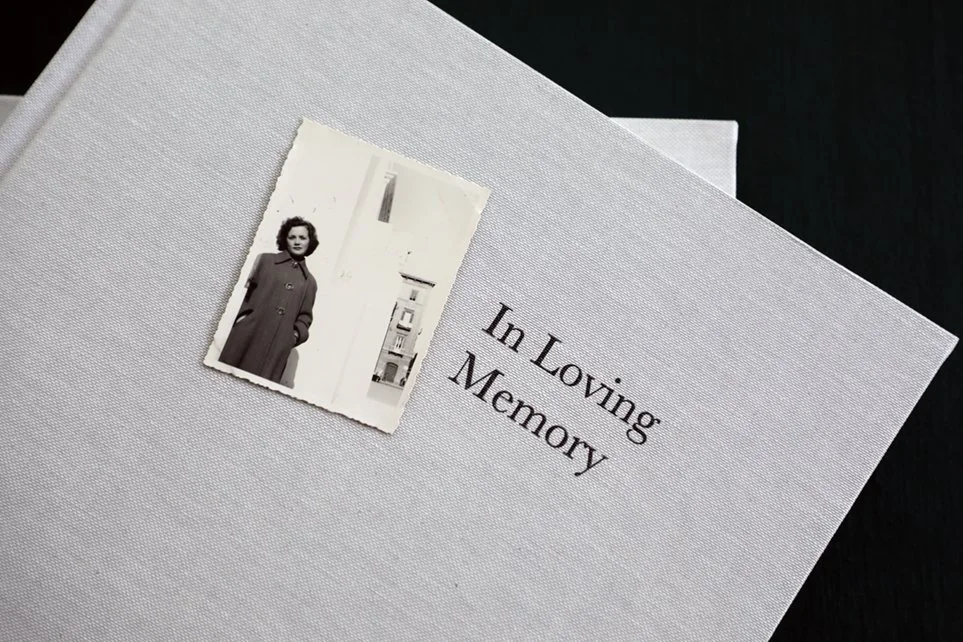

Challenge 3: Should I include captions in my memorial tribute book?

Always remember that what ultimately makes it into print in your memoir is 100-percent YOUR decision—so while I (and other personal historians or editors) may encourage you not to skip over your challenges, you are the one who gets to make that call.

“Let’s cut all ‘the hard stuff.’”

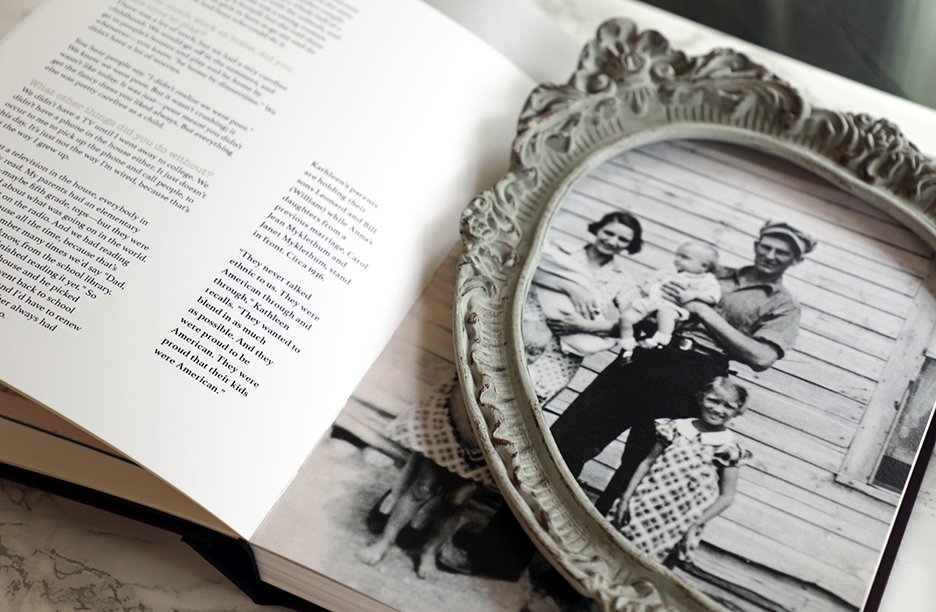

I conducted a series of in-depth, thoughtful interviews in which my client—let’s call him John—allowed himself to be vulnerable. He was a vivid storyteller and was comfortable going deep, talking about personal failures in addition to successes. He told of paths not taken that he now regretted; of teenage exploits that were, shall we say, less than innocent; and of a red-hot temper that caused him some problems in his twenties. Through our probing conversations, John spoke of lessons learned through his experiences, and of newfound meaning he was able to make from revisiting his earlier years. “This has been a profoundly rewarding experience,” John told me.

Then, when it came time to review the final manuscript of his life story, he made a decision I did not agree with: He wanted to cut all “the hard stuff” from his book.

Let me say that we had taken great pains to write these stories in a way that made them both compelling and, if not exactly didactic, at least revelatory. We wove in lessons learned, and nuggets of “John’s wisdom” throughout. He was at first “all in,” as was his wife, who had been an early reader. And then, he wasn’t.

When I asked him why he did not want to include stories of his challenges, he said that his descendants would think less of him. There was one granddaughter in particular, then a mere toddler, who he fervently “did not want to disappoint.” Arguments from me and his wife that those were the very stories that showed his humanity, that provided lessons for the next generation, that felt universal…well, all those arguments fell on deaf ears. “I would not want to know these things about my own grandfather,” he said plainly.

Because I am here to help my clients create the books they want—to help them define their legacies in the way they see fit—of course I ultimately followed his lead. His book was overflowing with funny anecdotes and light-hearted memories from his youth, for sure. It will undoubtedly be a treasure to his grandchildren.

But I did feel it was a lost opportunity to have passed down a book not also overflowing with wisdom; it was a Hallmark version of his life.

I find solace in the fact that his personal history interviews, while not fully reflected in his book, did help him ascribe new meaning to his life. (As I tell many people, the time spent allowing introspection in the interview phase is as much a gift to oneself as the book will be to one’s family; Mark Yaconelli calls this “feeling the grace of one’s own life.”)

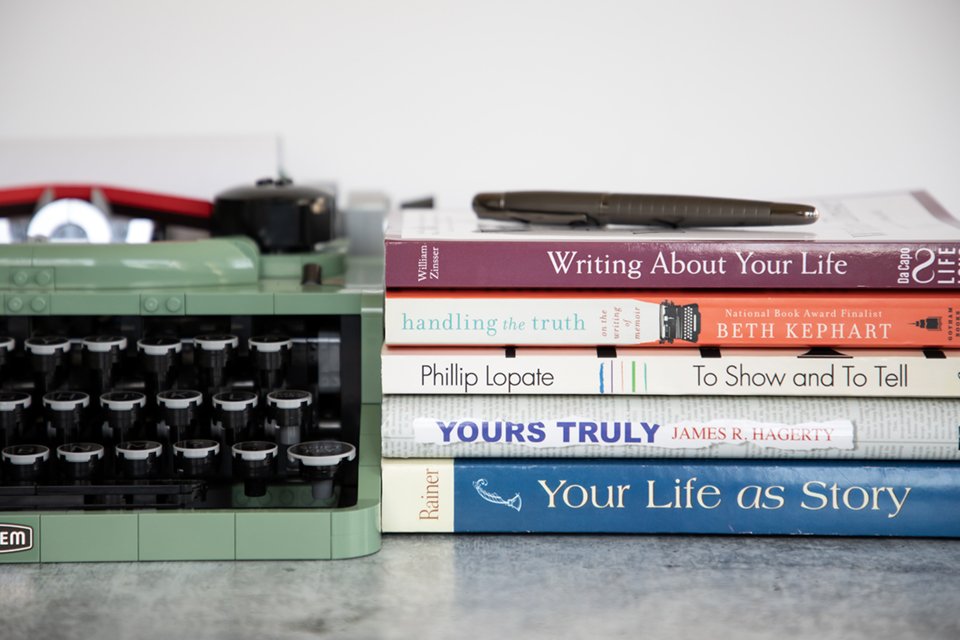

If you are ever on the fence about including tough times—anything from small failures to serious trauma—consider these words from Tristine Rainer (from her book Your Life As Story):

“Yours may be the words that relieve another’s isolation, that open a door to understanding, that influence the course of another’s path. If you write an autobiography for a great-great-grandniece not yet born, perhaps she will find it in her mother’s drawer, and she will be altered, perhaps even saved, through the wisdom you have sent her.”

And if you are ever reluctant to “go deep” in your writing, ALWAYS remember that it is your prerogative, and your prerogative alone, what to keep and what to cut. You are always your final editor.

Writer’s block can happen to the best of us. This simple idea—keeping a notebook of self-generated writing prompts—will keep your memoir ideas flowing.

Looking for a meaningful gift for your parents? An annual subscription to our Write Your Life memory and writing prompts may be just the thing—or, maybe not.

Learn about our Write Your Life course, providing memory prompts, writing guidance and a dose of inspiration to anyone who wants to preserve their stories now.

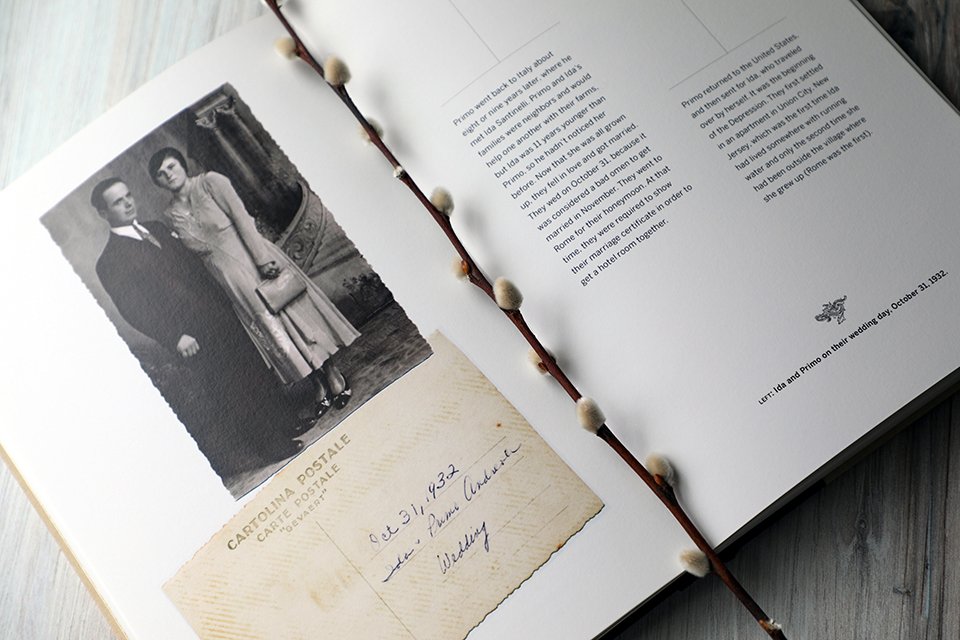

Here’s one time I gave in to my client’s preferences that still haunts me: Why we did not identify people in any of the photos in their family history book.

While your memoir is telling your stories in your words, a family tree chart outlining your relationships has a real place in that book—here’s why.

The first draft of your life story is likely to include some stuff you decide to cut later—but should none of your challenges make it into your final book?

Good writing prompts will rid you of blank-page anxiety—and you can easily write your own! Here, 5 steps to drafting a library of personalized memoir prompts.

While a journal called “Memories from Mom” or “Grandma’s Life Story” may be brimming with good intentions, the fact is that most of them remain mostly blank.

While all five of these books add value to any memoirist or life writer’s library, I’ve identified which is best for you based on your goals and experience.

A love letter (or book!) overflowing with memories makes a thoughtful anniversary gift. Here, 14 writing prompts to help you honor—and surprise—your partner.

Wondering if 52 weeks of memory prompts will help YOU write about your life at last? Here, answers to the most commonly asked questions about Write Your Life.

Every week you’ll get themed prompts to stir your memories, tips to write your stories with ease, and more! A unique gift for your loved one (or yourself)!

Sometimes all it takes to get unstuck with your personal writing is paying attention. Here are some easy (fun) ways to come up with journal writing prompts.

Ready to edit your family history or life story book? Follow these three tips from a personal historian to ensure everything is clear for your descendants.

This new book by Ruta Sepetys, You: The Story, is a great tool for those who want to use their own life experiences to inform their fiction writing.

Have you ever thought about what will happen to your diaries—who will read them, how you may one day use them? Join me as I consider this profound question.

Photos that have no captions will leave readers of your heirloom book guessing. Make sure to write captions that either tell a story or provide vital details.

Smells (such as of Mom’s perfume or Grandpa’s grease-stained clothes) and sounds—especially music—can trigger long-buried memories helpful for writing memoir.

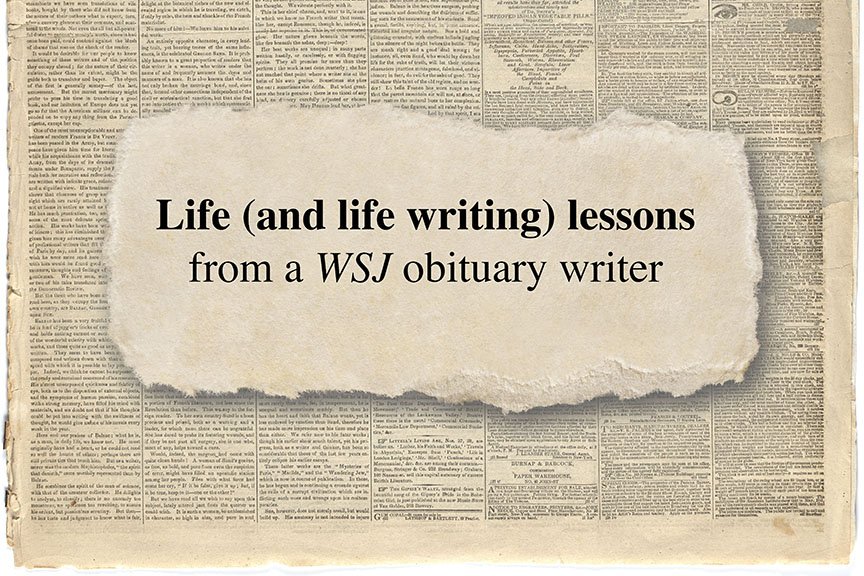

Why leave your legacy in the hands of someone else? Try your hand at writing your own obituary with these tips—it just may be the start of your mini memoir.

Don’t let all those memory-keeping ideas swirling around your head overwhelm you. Instead, take some time to hone in on which stories to tell first—here's how.

Ethical wills—also called legacy letters—are great ways to pass on values and life lessons to your descendants. These two books will help you create your own.

Any life story book passed down to the next generation is a gift—but it's an even better gift if it sounds like the real you: Write with your authentic voice.

Research and fact-checking are integral parts of creating your memoir—but there's a good chance that it may be getting in the way of your actually writing it.

I might not have time for the full-fledged memoir I want to write, but I can make time every day for this easy and significant journal exercise—and so can you.

If writing your memoir means enough to you to put it on a bucket list, please read this—I’ll help you easily move it from future project to present-day endeavor.

Want a life writing prompt that gets your pen moving AND delivers a trove of future ideas for your memoir? Here it is—and bonus, it's a fun one!

Ignore those naysayers who warn that you must be passed middle age to begin writing your life stories: Start your memoir now, no matter how old you are.

Sometimes a life writing project can become overwhelming—so much so that we stop writing at all. Get back on track with your memoir with this three-step reset.

Three easy ways to make memoir writing more approachable—and more efficient, so you can finally fit it into your busy schedule.

Go beyond a memorial slideshow and honor your lost loved one in a more permanent way. These three ideas for tribute memory books are easier than you think.

A love letter (or book!) overflowing with memories makes a thoughtful anniversary gift. Here, 14 writing prompts to help you honor—and surprise—your partner.

You've just returned from a family trip and know you want to make a travel memory book—just not right now! Follow these easy steps so you'll be ready later.

Want to make creating a travel book easy when you return from your family vacation? Follow these steps for easier—and elevated—post-trip memory-keeping.

Whether your family heirloom collection consists of generations’ worth of antiques or a handful of sentimental items, catalog them for the next generation.

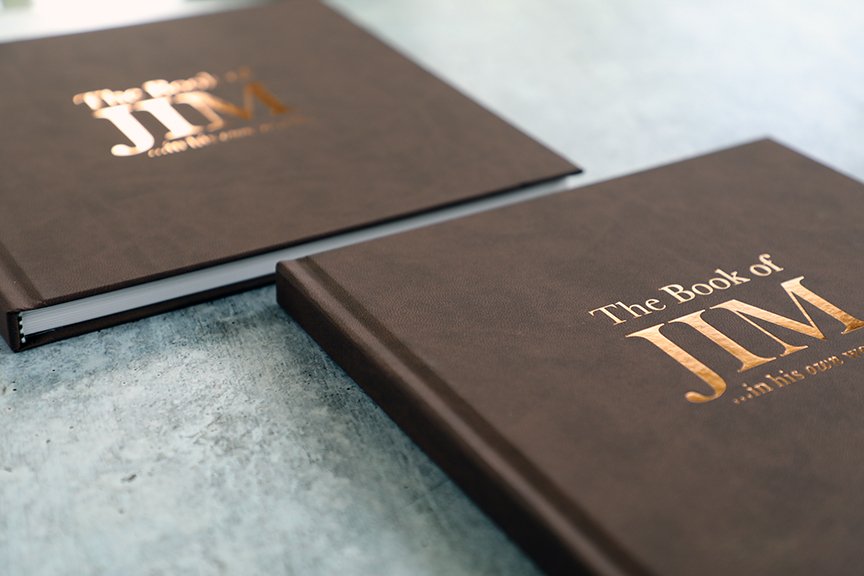

Here’s how to make a tribute book for their milestone birthday—your step-by-step guide to the most unique, thoughtful gift you can give someone you love!

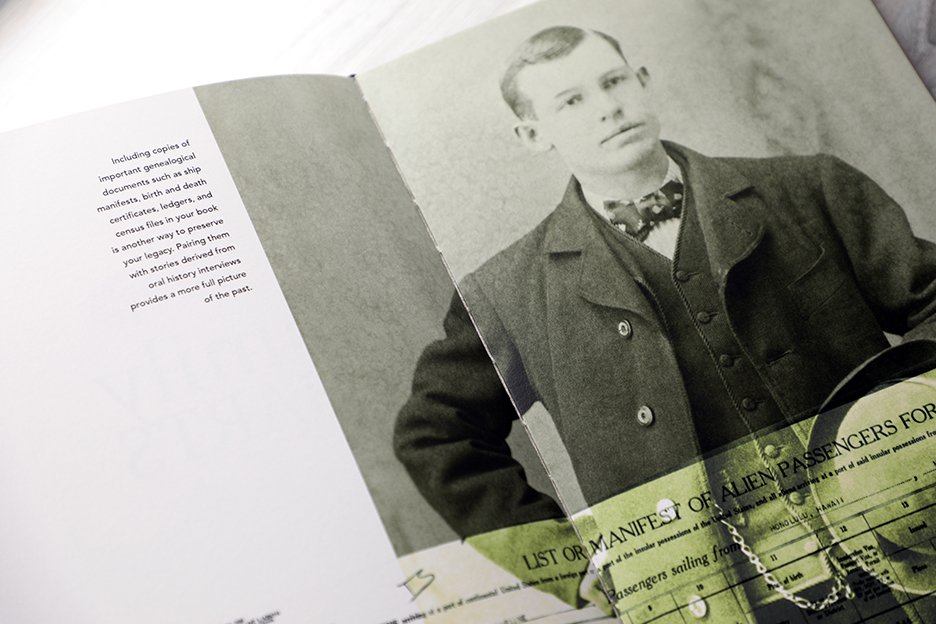

After we record your personal history interviews, I craft your story and photos into an heirloom coffee table book—not a video, not an audio file. Here’s why.

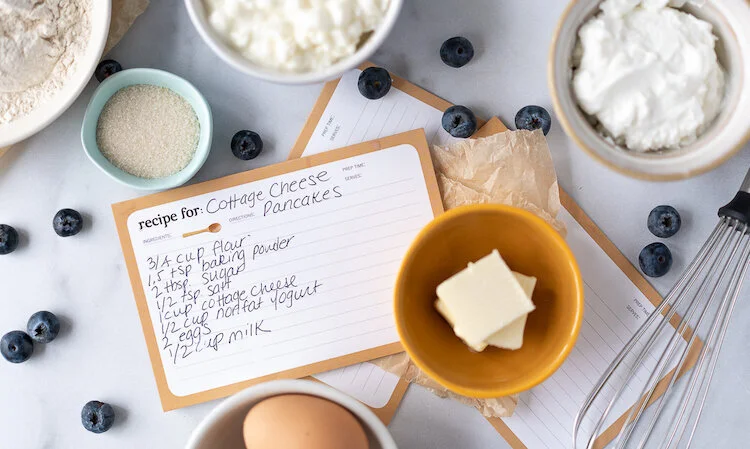

From gathering recipes to editing, from design to printing, these steps will walk you through how to create a family cookbook to preserve your food heritage.

From life story books to a family history collection, from travel journals to heritage cookbooks, our founder lists 10 of her favorite heirloom book themes.

A family photo book without captions is nice—but one with captions is an heirloom. A primer on what type of captions to include and how to design them cleanly.

Give your loved ones a gift they will cherish for years to come—one that puts memories front and center. Here are 3 (doable!) ideas to inspire happy tears.

The best posts to help you with memory-keeping, including family history questions, memoir writing tips, family photo preservation ideas & heirloom book themes.

If you’ve wanted to create a surprise tribute book telling your loved one JUST how special they are but cost is a factor, consider asking contributors to chip in.

These 3 photo book themes make it easy to show someone how much they are loved! Perfect for surprise birthday and graduation gifts—or just because.

Knowing your family’s recipes are preserved for the next generation is reassuring. Adding stories and photos, too, brings your food heritage to life. Start here.

When you want to cap off a milestone birthday party with a most meaningful gift, consider an heirloom birthday tribute book oozing with love and memories.

Writing a tribute book is a meaningful way to create a lasting legacy for a lost loved one. These expert tips from a personal historian will help.

Show her she is cherished with these unique Mother’s Day gifts that provide your mom with the sacred space to talk about and preserve her memories and photos.

If you would like to document your family stories in an adoption journey book, here is a road map for what to save, how to record memories, and when to begin.

Our food memories—sneaking tastes of Nonna’s sauce from the pot, learning to grill ribs from Dad—are worth preserving. Ideas to easily capture stories & recipes.

Searching for a groom gift beyond the traditional watch or cufflinks? Surprise him with an heirloom book expressing your love and gratitude—meaningful, unique.

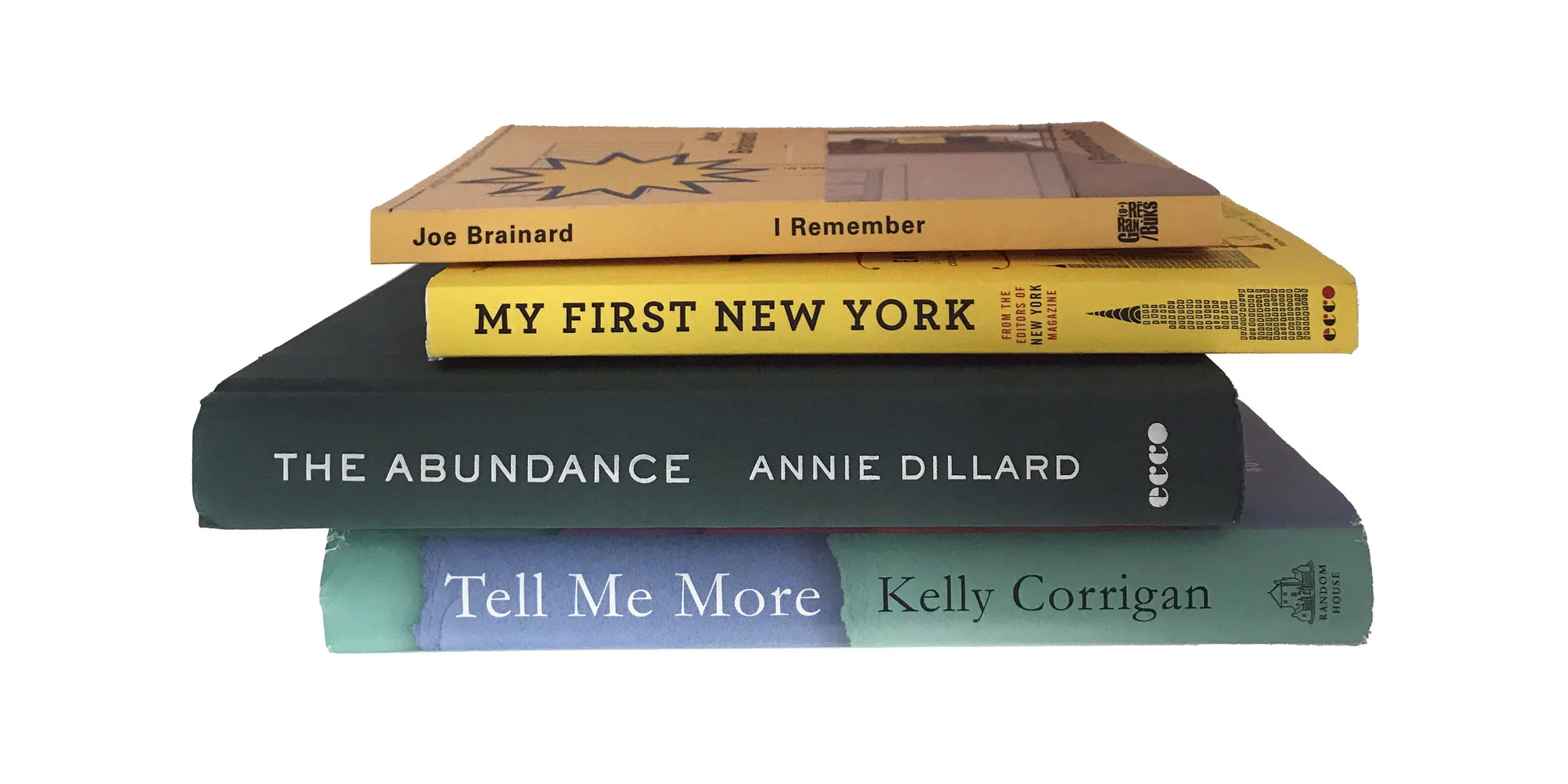

Memoir reading suggestions to inspire your own vignette-style life story writing, from Annie Dillard and Kelly Corrigan to Robert Fulghum and Sandra Cisneros.

In Part Two of our Life Story Vignettes Writing Prompts series, guidance on conducting a probing self interview as an entry point to your stories and memories.

In Part One of our Life Story Vignettes Writing Prompts series, we offer five specific exercises for writing about your memories by engaging all your senses.

Preserving the full story of your adoption journey may mean sharing some of the pain, too—but how much you include is a personal decision. We can guide you.

Do you want to preserve your family stories, but have no idea where to start? We’ve got six special life story book ideas to spark your imagination.

Modern Heirloom Books founder Dawn Roode on her journey from national magazines to bespoke life story books, plus the new signature product lines of books.

Sometimes it’s not a long narrative that most interestingly tells your story, it’s a simple list. How to use lists to add texture to your life story heirloom book.

No one will tell your life stories but you. Start with one, & go beyond sharing it: Do something with it! 5 ideas for preserving one chapter of your life story.

Nine reasons why preserving your family’s story in an Adoption Journey book is a worthwhile investment, including making it part of your Gotcha Day celebration.

Is there ever really a ‘right’ time to start writing your memoir? There’s not, in my opinion, but here are two questions to ask yourself to help you decide.